Reflections of a Midlife Millennial

December 16, 2021

In less than a week I turn 40. That’s 14,600 days, 350,400 hours, and 21 million minutes since I was lucky enough to be born to my parents, in Toronto, in Canada, in 1981.

Now, for many readers, the fact that I’m turning 40 may come as a surprise.

Most people I meet for the first time think I’m barely 25 years old, maybe 30. In fact, in a recent national survey conducted by our team at Abacus Data, we asked a representative sample of Canadians to guess my age. The result came back as expected – almost everyone underestimated my age with the average age estimate around 30. By the way – thanks to the roughly 10% of people who thought I looked 20 or younger.

People thinking I’m younger than I am has been a part of my life from an early age. Family, friends, clients, students, and audiences a like marvel at my youthfulness. I’m often asked how I did it, but frankly, I have no idea. It may be a combination of good genes, and a relatively healthy lifestyle (minus all the ice cream), or it could be the litres of excellent Italian olive oil I’ve consumed over my lifetime.

Everyone says that after I turn 40, being young looking will have its advantages. I say it’s about time – looking so young has definitely not been an asset for the first 40 years of my life.

However, this fresh-faced guy is now officially an old millennial (or as some have termed a “Geriatric Millennial”). That’s right, I’m a member of that infamous generation that I’ve spent the last 11 years studying, exploring, and trying to figure out as a social researcher. I’ve given a hundred or more speeches or presentations on those born between 1980 and 2000, interviewed thousands in the surveys we’ve conducted, and now, as I step into my midlife, I’ve been forced to reflect on what it means to be a middle-aged millennial. In fact, as an avid cyclist, I even picked up a copy of this book.

WHY USE A GENERATIONAL LENS?

A few years ago, I was part of a panel discussion talking about political marketing and the future of a certain Canadian political party. A fellow panelist at that session questioned the value of generation as a tool for understanding political behaviour. To him, age was the least interesting variable that could be used to explain why people think and behave the ways they do. He brought forth the notion that those who have kids and own a home have far more in common, even if 20 years apart in age, than two people who are close in age but have different lifestyles or have reached different milestones in their lives. In some ways, I agree with him. A 50-year-old with children is likely to have different priorities than a 50-year old without kids. But his point overlooks a crucial element – and something my team at Abacus Data has spent a lot of time exploring – do the circumstances shared by those born around the same time influence the way they think and act?

Now this isn’t to say that life cycle (aging) doesn’t impact how one thinks or behaves. Certainly, priorities change as you get older. When I was 20, paying off my mortgage, thinking about retirement, or figuring out how to keep my grass green in the middle of the summer was the least of my worries.

However, being born in 1981 means I experienced many of the same influences, contexts, and environmental factors as others born around the same time. Our research, for example, finds that millennials were raised differently than previous generations. Think about the households they were raised in, their relationships with their parents, and the expectations bred into them from an early age. Millennials were raised by parents who acted as their agents, curated almost every minute of their days, and encouraged them to follow their dreams and make every minute on earth count. They got regular feedback from those in positions of authority, while the lines of authority themselves were blurred. They had access to decision makers, were far more influential in household decisions, and were regularly consulted to share their thoughts. The world was their oyster, and our families and society generally were there to help make our dreams come true. It’s no wonder than 85% of Canadian millennials agree that, while growing up, many people told them they could achieve anything. Optimism and hopefulness became part of their DNA. The experience during these formative years were far different from those experienced by Boomers or Gen Xers.

[sc name=”signup”]

Now think about what was going on in the world and Canada from the early 1980s to the mid to late 2000s. While 9/11 was a seminal world event, millennials never really experienced an existential crisis that earlier generations had. The Great Recession in 2008 has certainly had an impact on their career progressions, but it didn’t influence behaviour and attitudes like the Great Depression had on my grandparents’ generation.

Instead, the big shift in our lives centred around the pace of technological change. On top of a very different upbringing, which alone would account for the generational gaps in expectations and outlook, millennials were the first generation to fully experience and grow up during the rise of the internet and digital technology as a whole. While a decline in deference was well underway since the 1980s, it accelerated because consumers, employees, and citizens had unlimited access to information that was previously controlled by a select few experts and those in the know. Millennials are the first digital native generation, but not the last. How we communicate, access information, and become informed about what’s happening in our world is fundamentally different. When we ask survey Canadians to identify their top breaking news source, the difference of opinion is profound. Upwards of 40 to 50% of millennials say they rely on social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram for breaking news. That’s about 25 points higher than all other Canadians combined and almost 40 points higher than Boomers. Now that’s a generational divide!

Canadian millennials are more likely to have traveled to another part of the world by the time their 30 than older generations. Half say they don’t believe in a god or higher power and almost half of millennial men are the primary cooks in their household. More millennial women will get a post-secondary degree than millennial men, a sharp change from earlier generations. These differences have an impact on our thinking and choices, controlling for milestones or individual circumstance. Identifying those differences and then making sense of them, is what our work is all about.

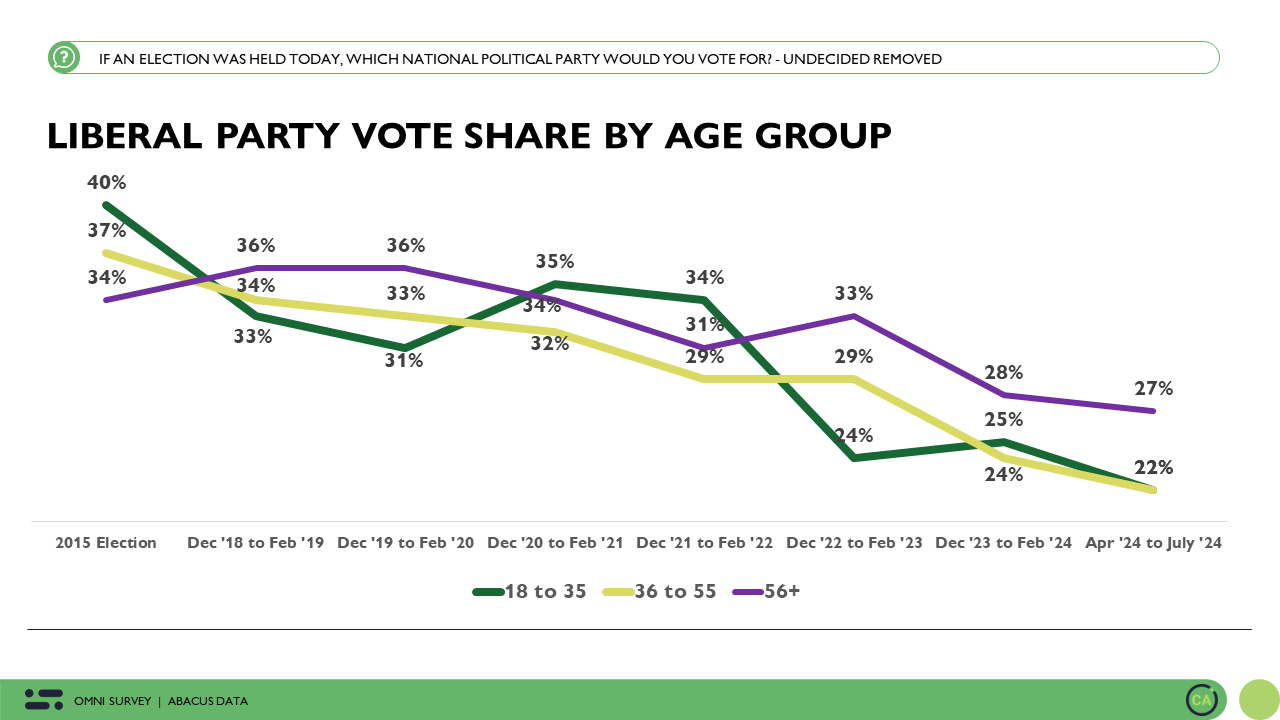

Millennials make up the majority of working age Canadians. They are increasingly taking leadership roles on teams and in organizations. They are the largest block of voters in the Canadian electorate, and a soon to be published book chapter I wrote finds that they were instrumental in all three election wins for Justin Trudeau and the Liberal Party.

MIDLIFE MILLENNIALS vs. YOUNGER MILLENNIALS

But in thinking about my milestone birthday, a question emerged – are old millennials much different than younger ones? Luckily, I run a twice annual survey of 2,000 Canadian millennials that I could dig into. Our latest survey – part of Abacus Data’s syndicated Canadian Millennials Report – was conducted in June 2021. The next wave is set to be fielded in January 2022.

First, a little about the mid-life or soon to be mid-life Canadian millennials (those today aged 35 to 41).

- Half of midlife millennials have kids. 40% are married.

- Only 35% feel they are living comfortably with almost half saying they live paycheque to paycheque. 1 in 5 old millennials have no savings at all.

- 60% own their home – 23-points higher than those aged 20 to 34. Among those who don’t currently own, 2 in 3 want to someday, even if more and more are becoming pessimistic about their ability to do so.

- 53% of midlife millennials have some money saved in an RRSP. 43% have an employer provided pension. Half have life insurance – 69% among those who are married.

- 71% own a car, 17-points higher than younger millennials.

- 20% own cryptocurrency.

Second, throughout the survey, the views, impressions and opinions of midlife millennials and their younger counterparts are quite similar. They are generally optimistic about the future (even in the middle of a global pandemic), are worried about the cost of housing, climate change, and the healthcare system, and generally approve of the job the federal government has done managing the country.

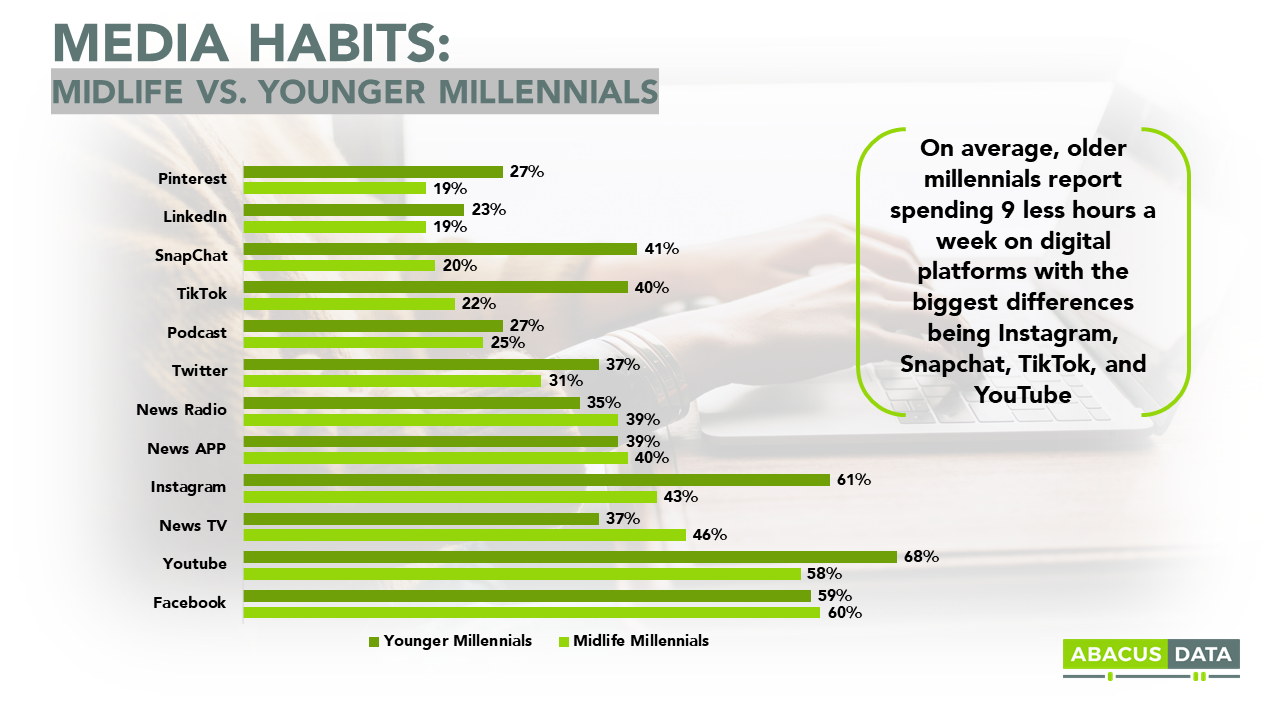

Where we do see some big differences between midlife and younger millennials is in their media use. Like many millennials my age, I have no idea what TikTok is for, how to use it, and what I’d even do with it.

Midlife millennials are as likely to check Facebook daily as younger millennials but much less likely to be using Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, or Snapchat. We are also 10-points less likely to be watching something on YouTube every day and more likely to be watching news on TV than younger millennials.

Overall, midlife millennials in Canada report spending nine hours less per week on digital platforms like YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter than younger millennials.

So, while life cycle helps to explain differences in homeownership, marital status, and financial situation, midlife millennials and younger millennials share the same outlook, expectations, and values, But are using different tools to engage and communicate.

40 IS THE NEW 30… RIGHT?

Despite my youthful complexion, I’m starting to feel and see the impact of my aging. There’s a little less hair on my head. My body takes longer to recover from exercise or sickness, and I’m increasingly finding myself not understanding what some of the younger members of my team or my students are talking about.

I’m lucky to have a job that lets me learn something new every day and engage with Canadians of all ages through the research we do. Cycling helps keep my mind sharp and body in shape and my friends and family (and Chestnut our dog) make life worth living.

As more and more millennials take that step into middle-age, they will bring the values, perspectives, and expectations they developed over the first 40 years and bring them into the workplaces, stores, and polling booths that they will increasingly influence over the next 40.

I always thought being 40 meant you were getting old. I’ve come to learn that it’s just another number. Although I do wish this number would stop increasing, it’s reassuring to know that I look about ten years younger to most people.

ABOUT ABACUS DATA

We are the only research and strategy firm that helps organizations respond to the disruptive risks and opportunities in a world where demographics and technology are changing more quickly than ever.

We are an innovative, fast-growing public opinion and marketing research consultancy. We use the latest technology, sound science, and deep experience to generate top-flight research-based advice to our clients. We offer global research capacity with a strong focus on customer service, attention to detail and exceptional value.

We were one of the most accurate pollsters conducting research during the 2021 Canadian election following up on our outstanding record in 2019.

Contact us with any questions.

Find out more about how we can help your organization by downloading our corporate profile and service offering.