The Future of Arts Education in the Age of Precarity

November 24, 2025

Last week, I had the privilege of speaking at Wilfrid Laurier University about the future of university education. It’s something I think about a lot. And it’s directly related to a research area I’ve been spending a lot of time exploring, and writing about (I’m even considering writing a book about it).

I call it the precarity mindset. It is a way of thinking that grows out of years of economic strain, global instability, and the rapid advance of technologies that most people still feel they cannot fully understand or control. For many Canadians, it is no longer a question of whether there will be enough to get by. It is a deeper and more existential worry about whether we will be ok at all.

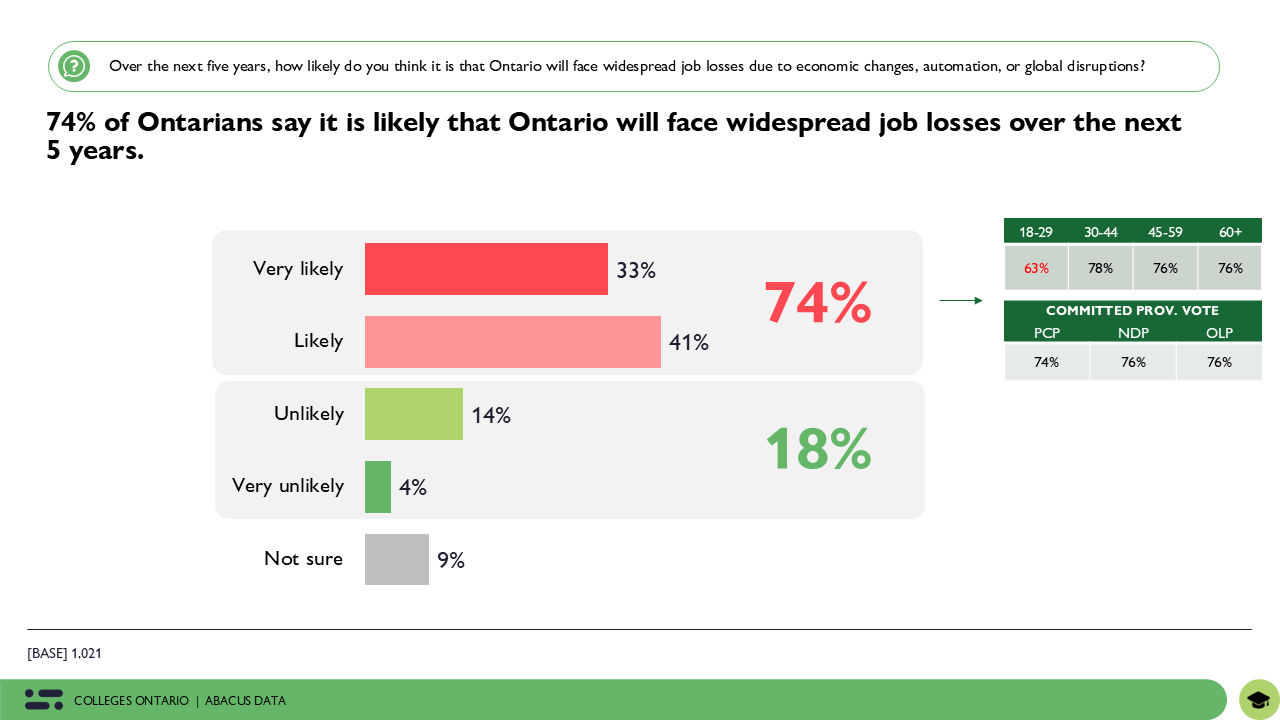

In the work we do at Abacus Data, these worries come through clearly. More Canadians are anxious about meeting basic needs. Many are delaying life decisions because the future feels unpredictable. When we ask people what keeps them up at night, they talk about inflation and housing, but they also talk about war, political division, misinformation, and I think so, more will cite their fears about what artificial intelligence will mean for their jobs and their children. Nearly half of Canadians say they use AI tools regularly, but a majority do not trust the technology. Six in ten believe AI will destroy more jobs than it creates. Only a small share believes they will personally benefit from the wave of innovation they keep hearing about.

This is the mindset universities are working within today. The shift from scarcity to precarity changes how people think about education. Scarcity is about short term survival. Precarity is about long term uncertainty. It is about a desire for institutions that do more than prepare students for a job.

People want institutions that help them see a path forward in a world that feels chaotic.

They want reassurance that the choices they make today will still matter in five or ten years.

They want education that helps them adapt, not just qualify.

That reality creates a powerful opportunity for universities. It also creates urgency.

Universities need to become engines of national optimism. They need to be places where students learn to understand a complicated world, where they gain skills that can evolve as the world changes, and where they build the confidence to move through uncertainty with a sense of agency instead of fear. This is not just a matter of messaging. It is about the substance of what universities teach and how they teach it.

The arts and social sciences are central to this work. I say that not only as a researcher who spends his days analyzing public opinion, but as someone with three social science degrees and fourteen years of teaching experience at Carleton University. My entire career has been shaped by what I learned in political science and public affairs. Those programs taught me to make sense of complexity, to understand how systems behave, to solve problems without clear answers, and to communicate ideas clearly and responsibly.

These are the exact capabilities Canadians need in the AI age. They are not soft skills. They are survival skills in a time when information is multiplying, institutions feel wobbly, and technologies are developing faster than our social norms can keep up. AI is not just a STEM topic. It is already changing how we think about truth, trust, identity, creativity, and fairness. Those questions live at the heart of the arts and social sciences.

The students who will thrive in the future are not the ones who only know how to code or analyze data. They are the ones who can ask better questions. They can understand context, anticipate consequences, and make ethical decisions. They can collaborate with others and communicate ideas in ways that build trust. These are the strengths that come from studying history, sociology, psychology, political science, philosophy, literature, and the many other disciplines that help us interpret the world around us.

If anything, the precarity mindset makes the arts more valuable than ever. Students are not just trying to build a career. They are trying to build a life in a period of constant change. They want a sense of direction and a framework to understand the forces that shape their choices. They want tools that will help them adapt as technologies disrupt industries again and again.

The challenge for universities is to talk about the arts and social sciences with confidence. These programs build resilient citizens. They help people navigate uncertainty. They deepen our understanding of society and give us the vocabulary to solve complex problems. They make democracy stronger and communities more cohesive. They allow us to stay human in a world where machines are becoming more capable by the day.

The future of universities will not be defined by how quickly they adopt new technology. It will be defined by how well they help people make sense of it. In the age of precarity, reassurance is not a luxury. It is a responsibility. And I think the arts are essential to delivering it.

David Coletto is founder and CEO of Abacus Data. Subscribe to his personal substack and tune in every week on his politics podcast over at the Hub Canada.