DIY ANCESTRY: Genetic Testing & Corporate Trust

January 24, 2019

The research cited below is sourced from an in-depth study of how consumers’ adoption of emerging technologies intersects with data privacy and public trust. If you would like to see more analysis from our work, please reach out to Executive Director ihor@abacusdata.ca for more information.

-Direct to consumer genetic testing driven by ancestry; health a tertiary consideration.

-Genetic genealogy industry grappling with trust deficit.

-Consumers more comfortable sharing genetic data than movement, financials, private messages.

Know thyself. Not just ancient Greek philosophy, but a marketing proposition genetic genealogy firms like 23andMe, AncestryDNA and MyHeritage are using to encourage consumers to try a new suite of at home testing services. In a departure from selling glossies to travel starved suburbanites, even National Geographic has gotten in on the action.

Having evolved in the last decade from the sole domain of labs & hospitals to an easy to use, saliva-based, direct-to-consumer offering, these genetic testing kits offer a seductive sell: a robust, scientific estimate of who you are, how you’re built, and where you’re from.

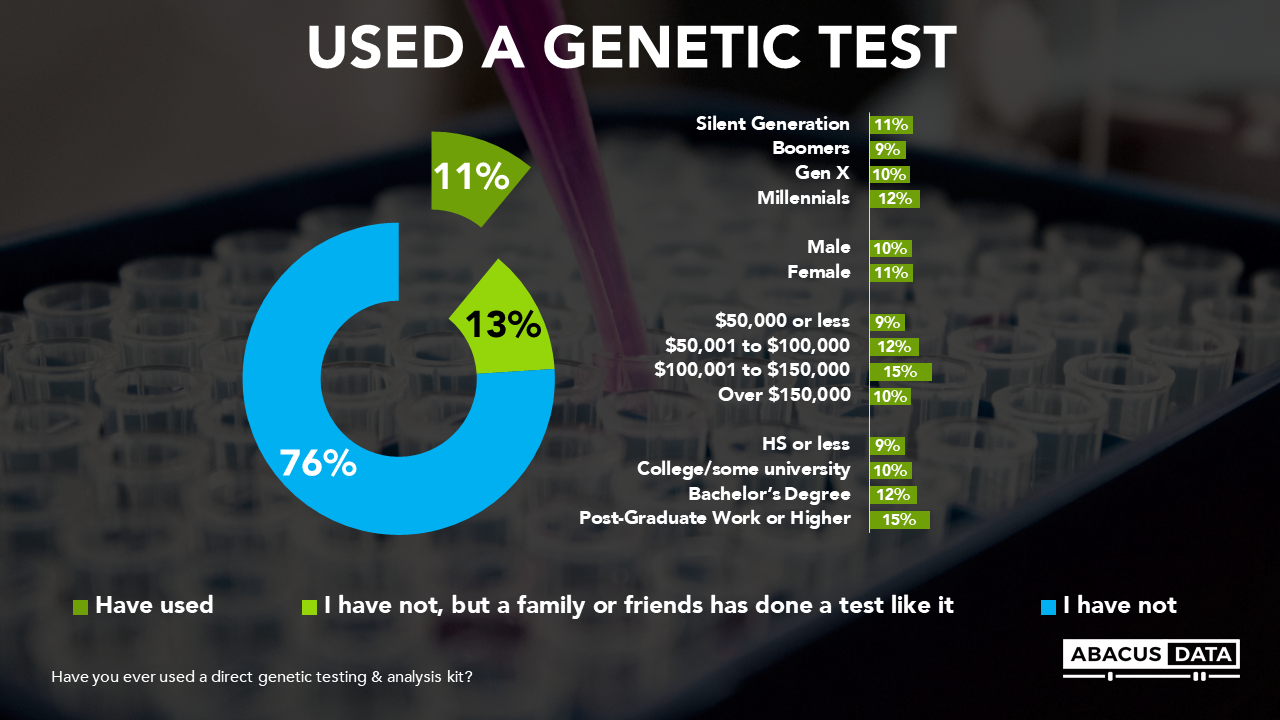

When we surveyed Canadians last summer (2018), about 11% of the adult population – (~3 million Canadians) – reported having used a direct genetic testing & analysis kits. Rich or poor, old or young, the technology has been used in equal measure by every group.

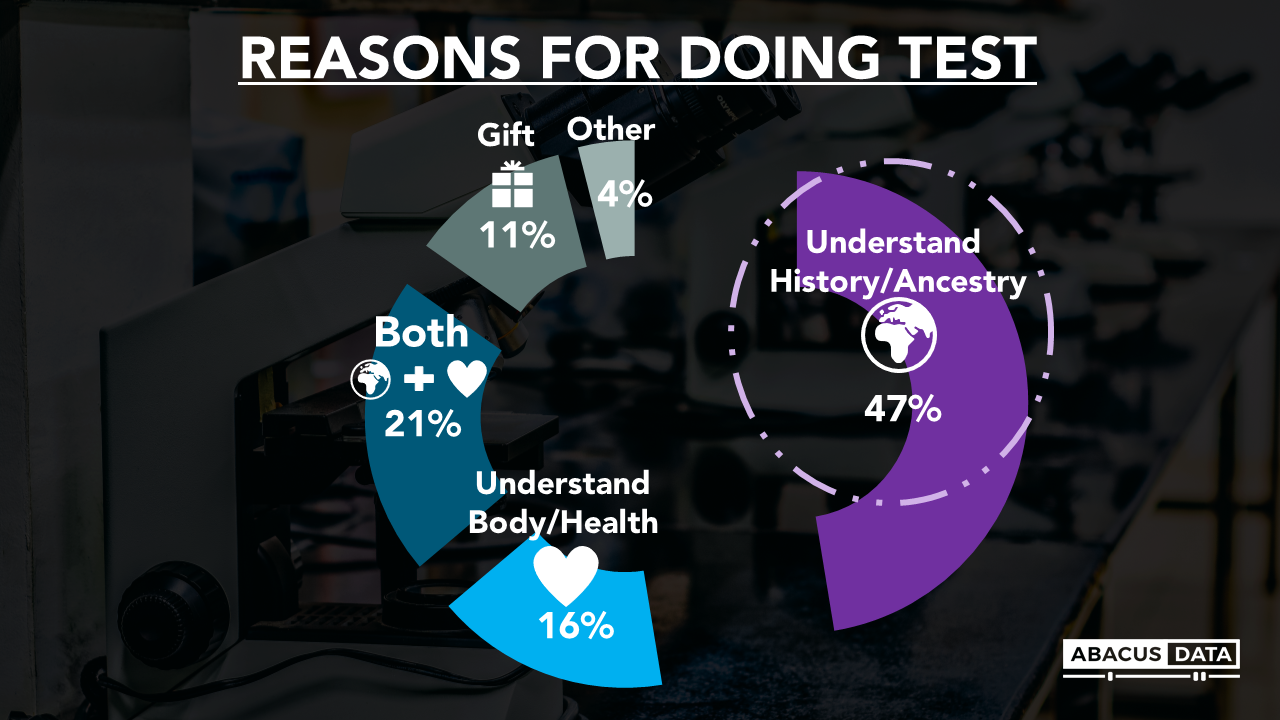

Though there are plenty of health applications, understanding history/ancestry is the big driver – the reason 7 of every 10 kit users ordered the test. Marketing at its core is an appeal to an individual’s identity. Have a product whose direct value proposition is telling you who you are and where you come from? Seems like an easy sell.

Yet in our age of data breaches and institutional trust deficits things are not so straightforward. Even if a life of crime or misattributed paternity surprises do not seem likely in your future, one could imagine why Canadians might be hesitant to trust companies with their data.

And so we surveyed those who have not taken the test to rate their feelings around the value proposition between several pairs of polarities, including whether in their view:

- There is more benefit to the consumer vs. more benefit to the companies collecting the data.

- The benefits outweigh the risks vs. risks outweigh benefits.

- Information is being kept securely vs. information is insecure.

- Information is used only for the benefit of consumer understanding vs. information is used in many other ways that benefit the company.

The prevailing sentiment is one where the fundamental trade off is seen as inherently tipped against the customer. More see risks than benefits, information is assumed to be unsecure. Crucially, consumers see far more upside for the companies on the receiving end of the data than they do for themselves. The balance of opinion swings the other way among test users, with many more believing that the technology benefits the consumer more than the company.

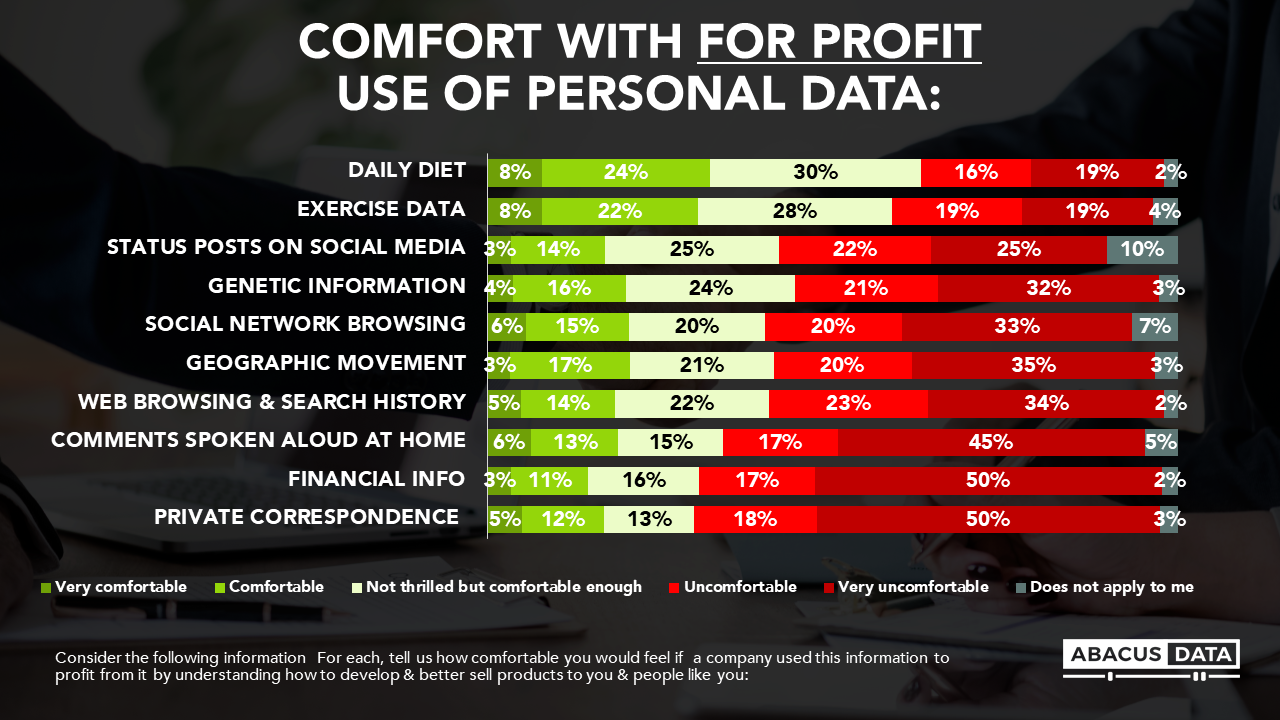

This attitude is not unique to genetic information. When we explored the relative comfort/discomfort Canadians felt with companies using various information sets for-profit, most were comfortable with the use of two health adjacent areas: daily diet and exercise data.

Genetic information is in a secondary tier of comfort along with social network activity – about half are opposed to corporate use of the information, while a little less than half are comfortable enough with it. It probably says something profound that financial information is considered far more sacrosanct in this context than your genetic code.

Despite these reservations, about 60% of the adult population in Canada were open to ordering a home kit genetic test. Most are in no hurry, and 18% would like to do one or are actively looking into it, leaving much room to grow for the sector.

This discussion exists in a specific cultural context – one where institutional trust is in decline, and data breaches raise public concern about the integrity of companies and the security of information. Public opinion is thermostatic and will shift depending on how much consumers perceive is being done on the part of regulators and industry to safeguard their data. If the scales are tipped towards an unregulated wild west, we will likely continue to see potential customers put up walls and assume the worst about industry’s intent. If industry can effectively demonstrate safety, responsibility and social benefit – with the “help” of regulators or without – expect these perceptions to decline.

Open up a business publication and you’ll often read something to the effect of “data is the new oil”. I find this a fantastic metaphor not due to the inherent validity of the claim, but because there is a parallel lesson in social license here. The resource industry (through much trial and more error) had the opportunity to learn many lessons over the decades on how central community buy in and public trust is to long term corporate health & profitability. For companies handling sensitive data, similar lessons exist, ones presently being learned by a certain social network. A proactive and consistent story of how these services could contribute to a social net benefit would go a long way in making Canadians more comfortable about the prospect of taking one of these tests.

Methodology

The survey was conducted online with 1,500 Canadian residents aged 18 and over from August 15th to 20th, 2018. A random sample of panelists were invited to complete the survey from a set of partner panels based on the Lucid exchange platform. These partners are typically double opt-in survey panels, blended to manage out potential skews in the data from a single source.

The Marketing Research and Intelligence Association policy limits statements about margins of sampling error for most online surveys. The margin of error for a comparable probability-based random sample of the same size is +/- 2.53%, 19 times out of 20.

The data were weighted according to census data to ensure that the sample matched Canada’s population according to age, gender, educational attainment, and region. Totals may not add up to 100 due to rounding.