The Shortage Economy in Canada and What it Means for Leaders

January 27, 2022

In its early October edition, the Economist put a spotlight on what it called the “shortage economy” and argued that “scarcity has replaced gluts as the biggest impediment to growth.”

As a public opinion and social researcher, I was of course intrigued.

And so, at the beginning of this year, I conducted a large national survey of Canadian adults (n=2,210) and explored several aspects of the economic and social experiences that the shortage economy may be having on Canadians.

Specifically, I wanted to try and answer two questions. How are Canadians experiencing the shortage economy and what does it mean for leaders?

This data is also part of a webinar I’m delivering with TEC Canada later today.

In my view, supply chain disruptions, empty shelves, and rising prices are a core part of the shortage economy. However, we also have to consider the impact of labour shortages, worker fatigue and burnout, and how all these factors are impacting both consumers and citizens (from a political perspective).

The implications of this research are pretty clear.

- Obviously, we will need to start learning to do more with less.

- But we need to also recognize that employees and workers are empowered (even if they don’t know it yet) and are coming to work with a different frame of mind. Many are tired, burned out, and looking for real meaning in their work.

- The customer experience has also changed. Labour and product shortages mean wait times are longer and full of friction than many have come to expect. The rapid shift to e-commerce has raised the bar to a standard that many brick-and-mortar retailers and service providers are having a challenge matching.

- We are moving more sharply into the politics of inflation – where public concerns focusing on the cost of living and the ability of political leaders to deliver relief are juxtaposed with budget deficits and fears of stoking inflation even more.

Overall, this is a very challenging environment to lead.

SHORTAGE ECONOMY: THE LABOUR MARKET

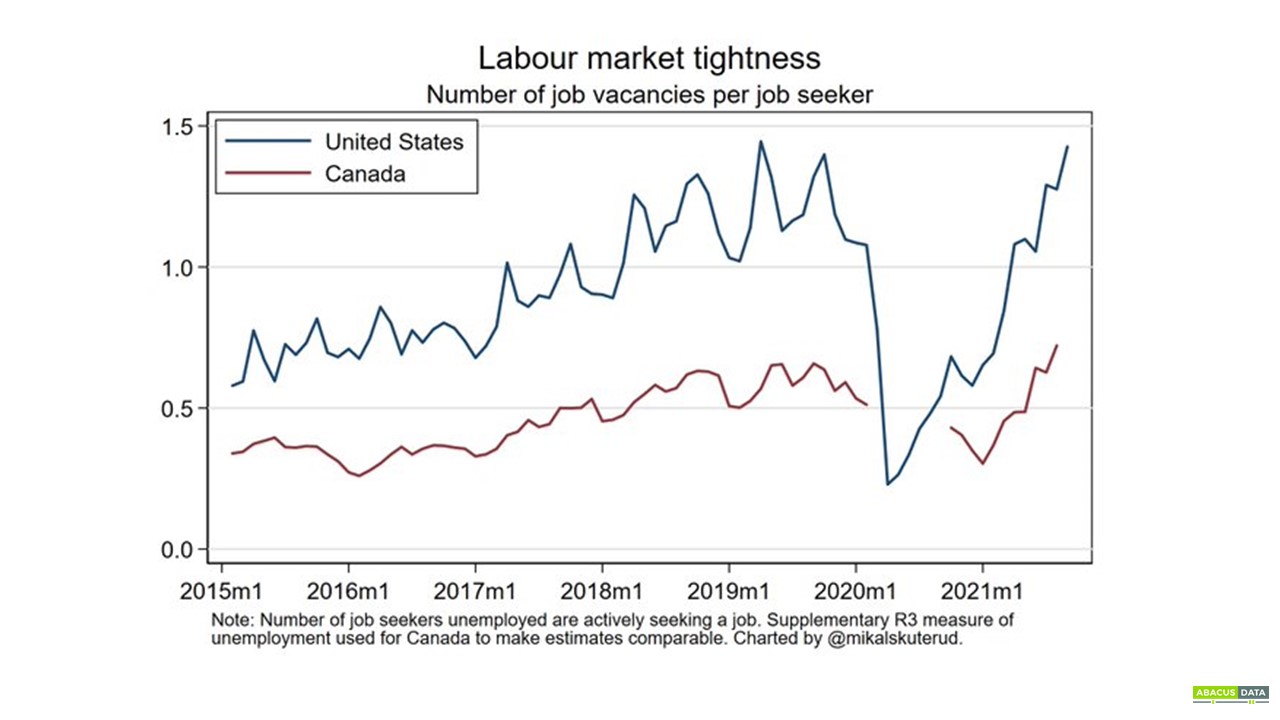

Although the “Great Resignation” took hold in the United States, evidence suggests the same phenomenon has not yet happened in Canada.

Labour participation rates rebounded far quicker in Canada and our labour market tightness (number of job vacancies per job seeker) is nowhere near where the United States is.

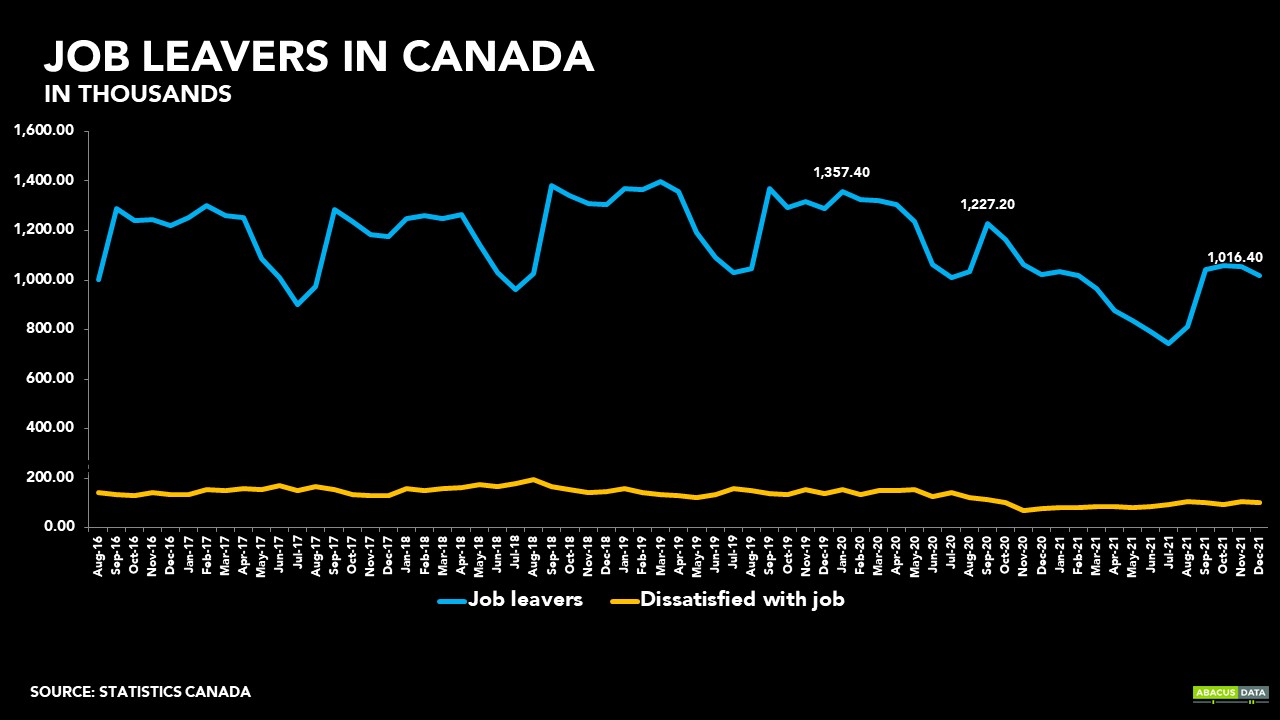

Moreover, Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey finds that the number of Canadians leaving their jobs voluntarily and because they are dissatisfied with their work, is much lower than it was at the start of the pandemic. It’s clear we aren’t seeing a “Great Resignation” in Canada.

In my survey, 18% of employed Canadians said they changed jobs in the past 12 months, including 9% who said they quit a job even when they didn’t have another one lined up. This behaviour was much more common among those under 45 – with 16% of 18 to 30-year-olds saying they quit without another gig ready.

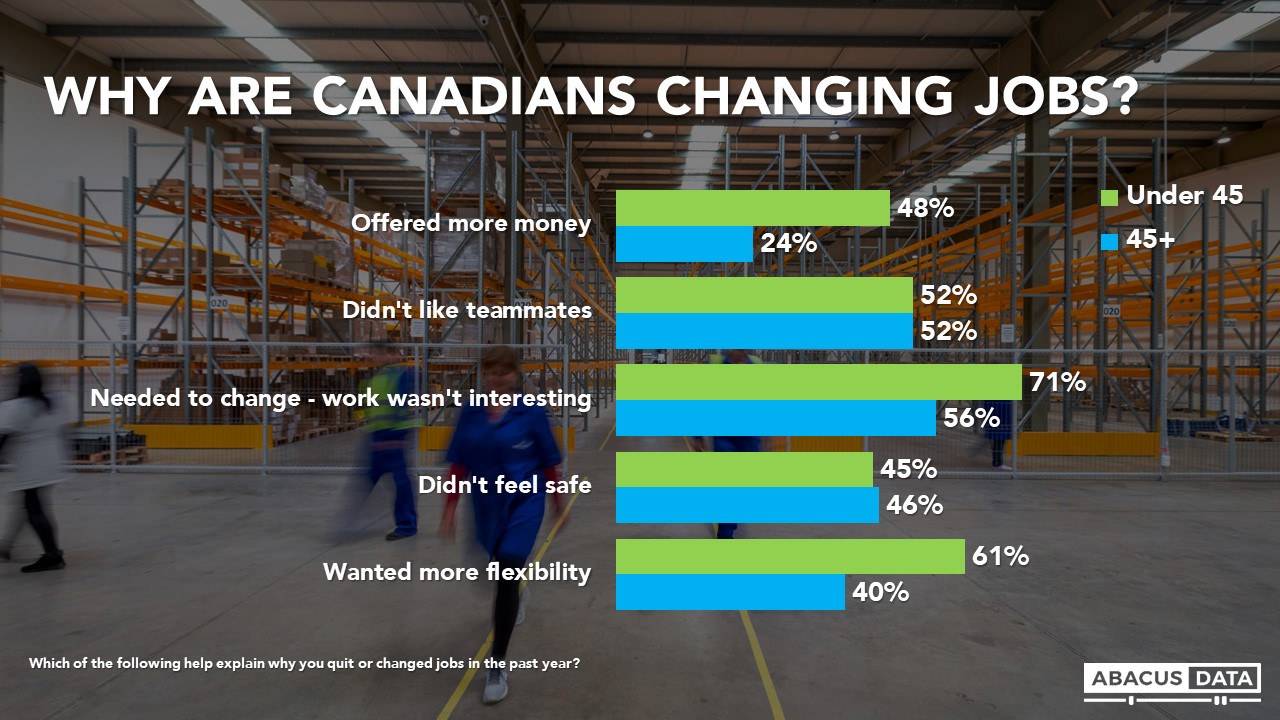

But more interesting in my data is the reason why people changed their jobs. Going beyond “dissatisfaction” as the Statistics Canada survey measures, I found that the top reason for job changers was they “needed a change – the work they were doing wasn’t interesting”. More than 60% of job changers cited this as a reason and it was the top reason for workers over and under 45 years old.

Younger job changers were more likely to report being offered more money – logical given younger workers are more likely to seek higher wages and promotions. But they were also more likely to report wanting more flexibility. Six in ten job changers under 45 reported the desire for more flexibility as a reason why they changed jobs. This is not new, but a preference the pandemic has made more possible than ever.

But it’s not just job switchers or a tight labour market that is impacting productivity and workplace culture. Millions of Canadians are feeling burned-out.

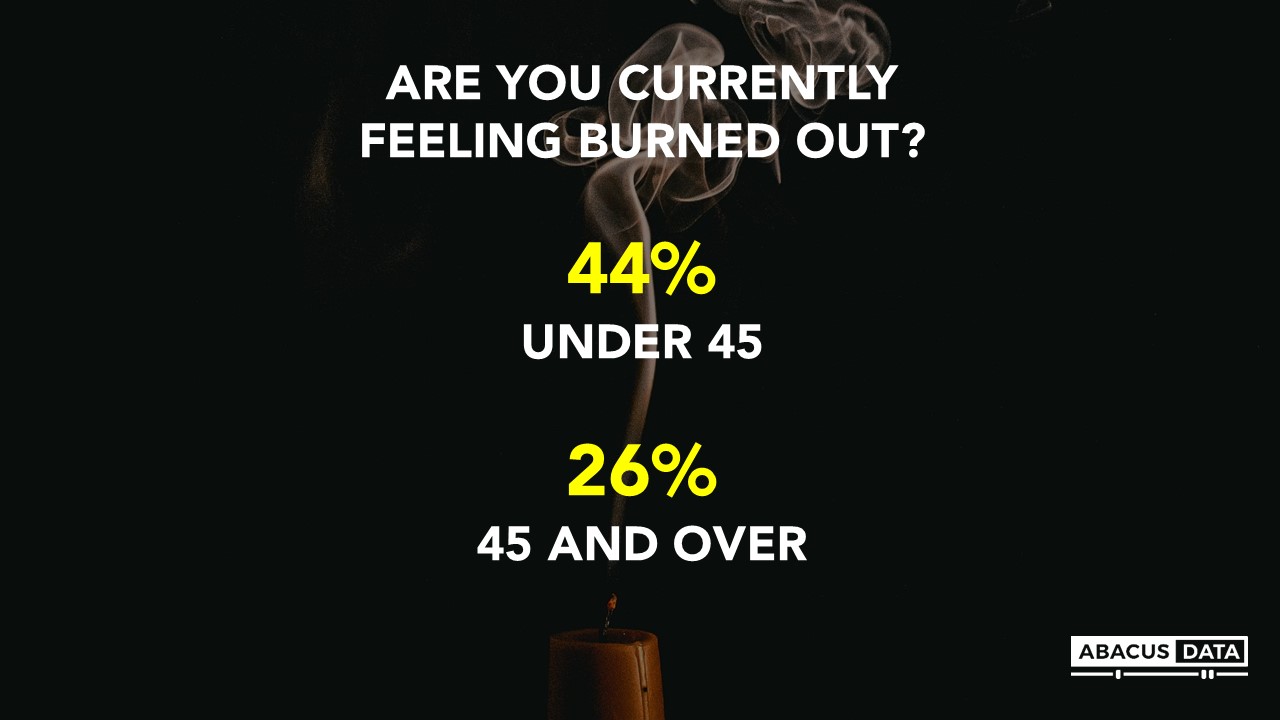

In my survey, 1 in 3 Canadians felt they were currently feeling burned out, including 44% of those under 45. To add some context, that’s 10 million or so people feeling burned out, just after the holiday season when many had the opportunity to rest and recharge.

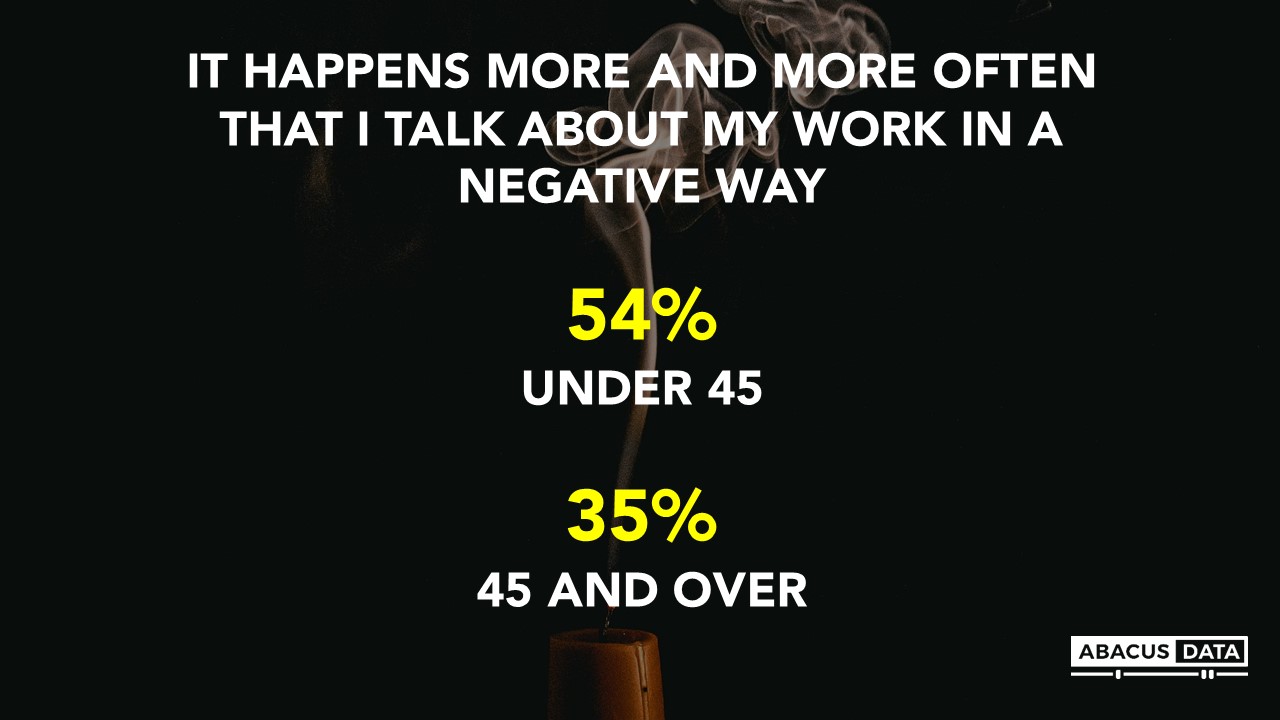

What does burnout look like? Most working Canadians agree that “there are days when I feel tired before I arrive at work” and half of those under 45 agree “it happens more and more often that I talk about my work in a negative way.”

If we haven’t yet seen a Great Resignation in Canada, these numbers suggest it could still come.

SHORTAGE ECONOMY: GETTING WHAT WE WANT AND NEED AND PAYING MORE FOR IT

We all know that the pandemic severely disrupted supply chains and Omicron has made things even worse. Everyone has an anecdote of how long it’s taken to get a new fridge, car, or even hire someone to renovate their home. These experiences are widespread, according to my survey.

Almost half of Canadians say they couldn’t get a product they wanted in the past 12 months because of a shortage or that product being temporarily unavailable.

Furthermore, 84% say this experience has been happening more often than usual.

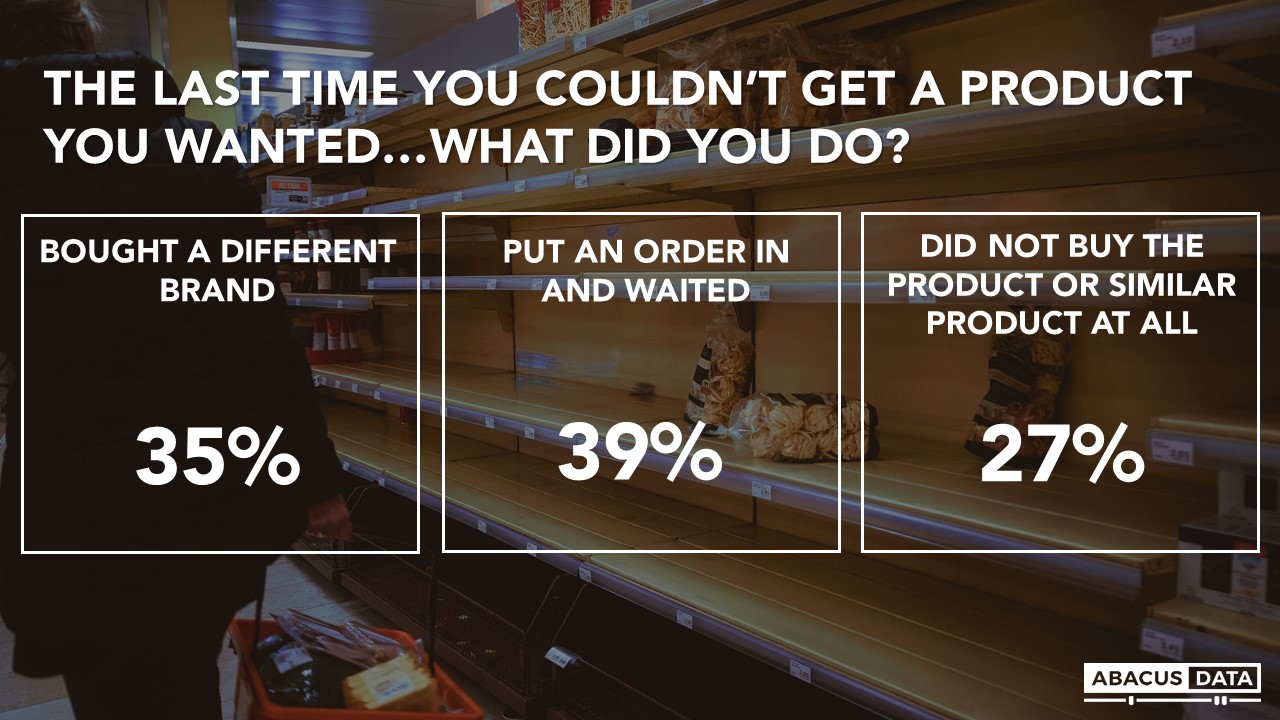

But what are Canadian consumers doing when they face an empty shelf or back-ordered product? It varies quite a bit. When asked what they did the last time they couldn’t get a product they wanted, 35% bought a different brand of the same product, 39% ordered the product and waited, while 27% didn’t buy the product at all. In all three, the consumer experience was disrupted.

While this presents itself as an opportunity for new brands to connect with consumers, it also forced consumers to wait, something they don’t appreciate all that much and likely left them feeling dissatisfied with the brand and retailer. For others, they simply didn’t buy the product, perhaps spending that money on something else.

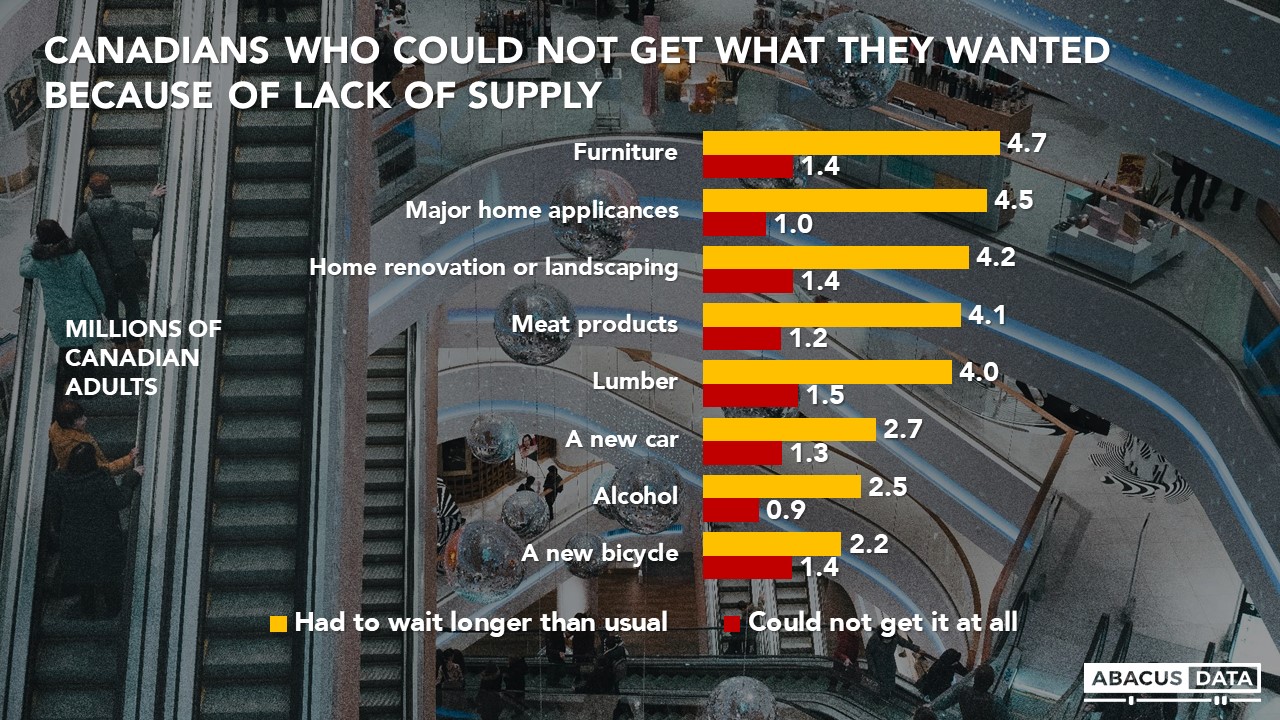

Disruptions like these were widespread and occurred across both product categories and services.

The chart below reports the estimated number of Canadian consumers (18+) who report being impacted by supply shortages. Millions of Canadians either experienced delays or didn’t get what they wanted at all when it came to furniture, major home appliances, meat products, lumber, or a new car. As someone in the market for a new road bike, I empathize with the 1.4 million Canadians who could not get that new bike they wanted thanks to a global bike component and parts shortage.

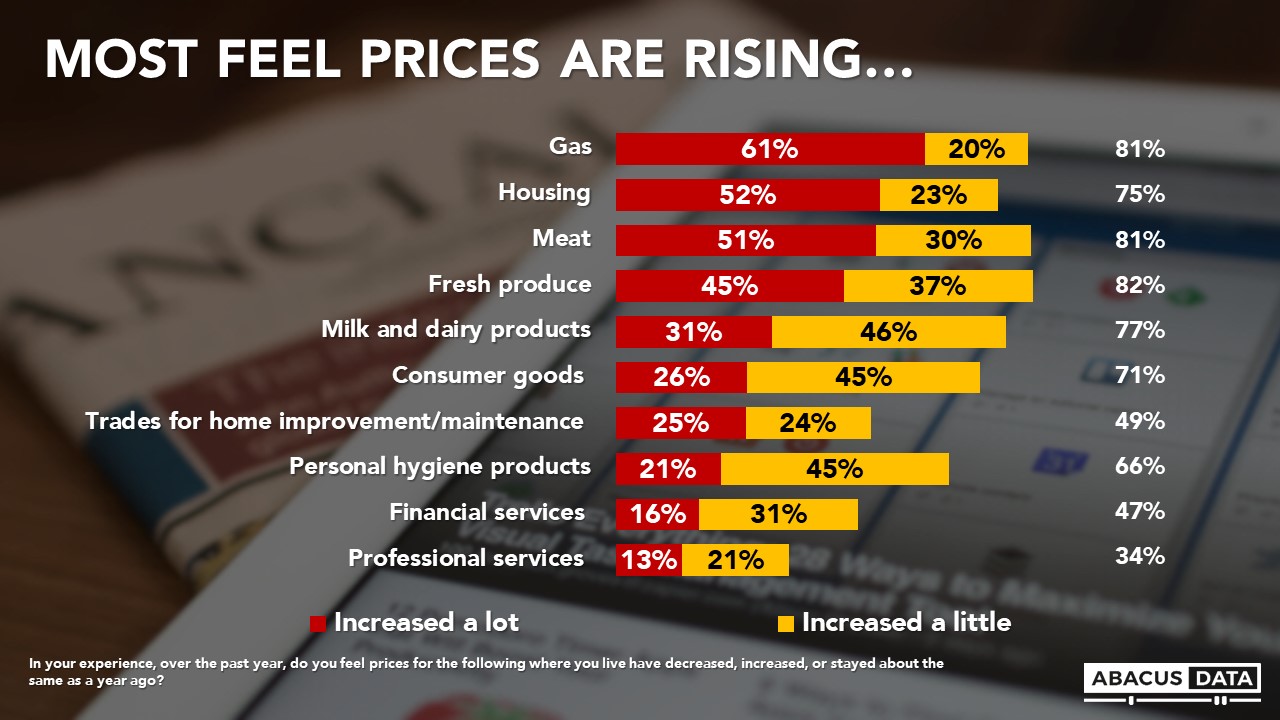

But the lack of supply didn’t just leave consumers frustrated, it also caused prices to rise in many consumer product categories. The cost of living is going up at its fastest pace in three decades, but more important than actual increases are the perceptions that prices are rising.

Most Canadians believe the price for many food products, gas, housing, consumer products, and even personal hygiene products are rising. Many also think the price they are paying for services such as the trades, financial services, and professional services are also increasing.

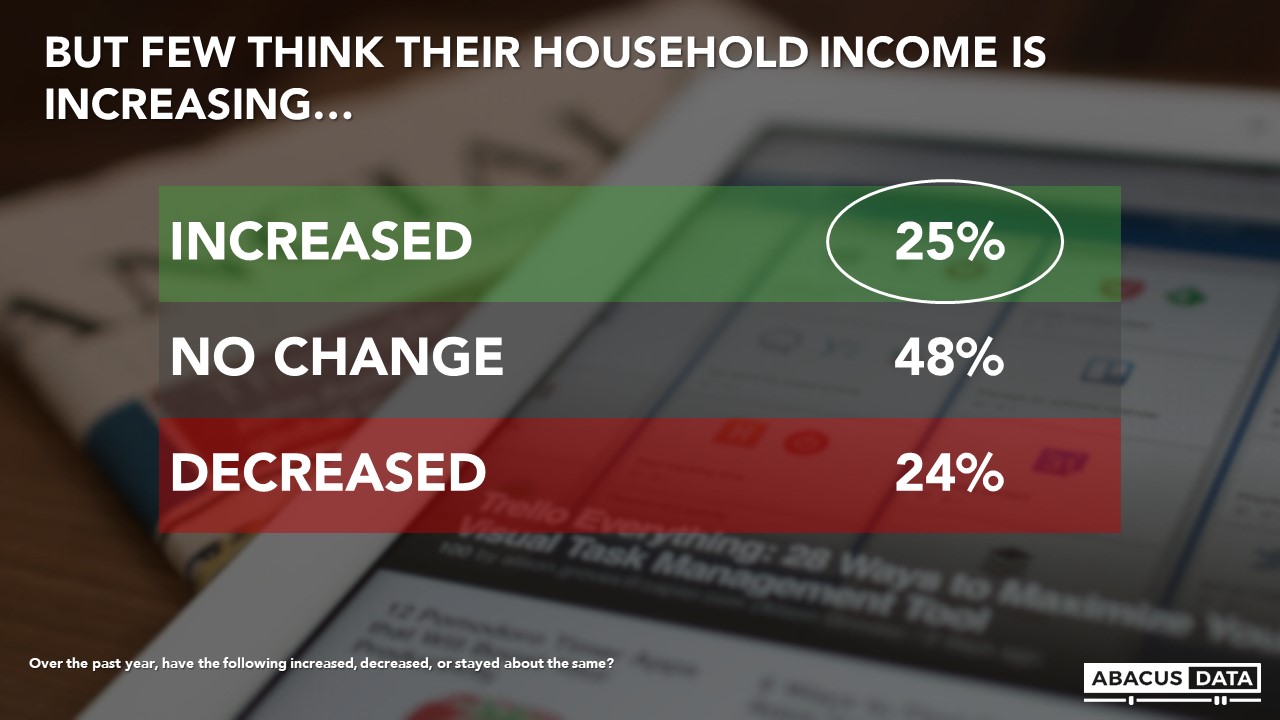

While people believe prices are rising quickly, few report their household income rising. Only 1 in 4 Canadians say their household income has increased in the past year, while a similar proportion feel their incomes have actually decreased.

The shortage economy in Canada has left many consumers dissatisfied – either because they couldn’t get a product or service they wanted or because they are now paying more for less.

THE DEATH OF CUSTOMER SERVICE?

But interestingly, the impact on the perceived quality of customer service has not been overly negative for most people.

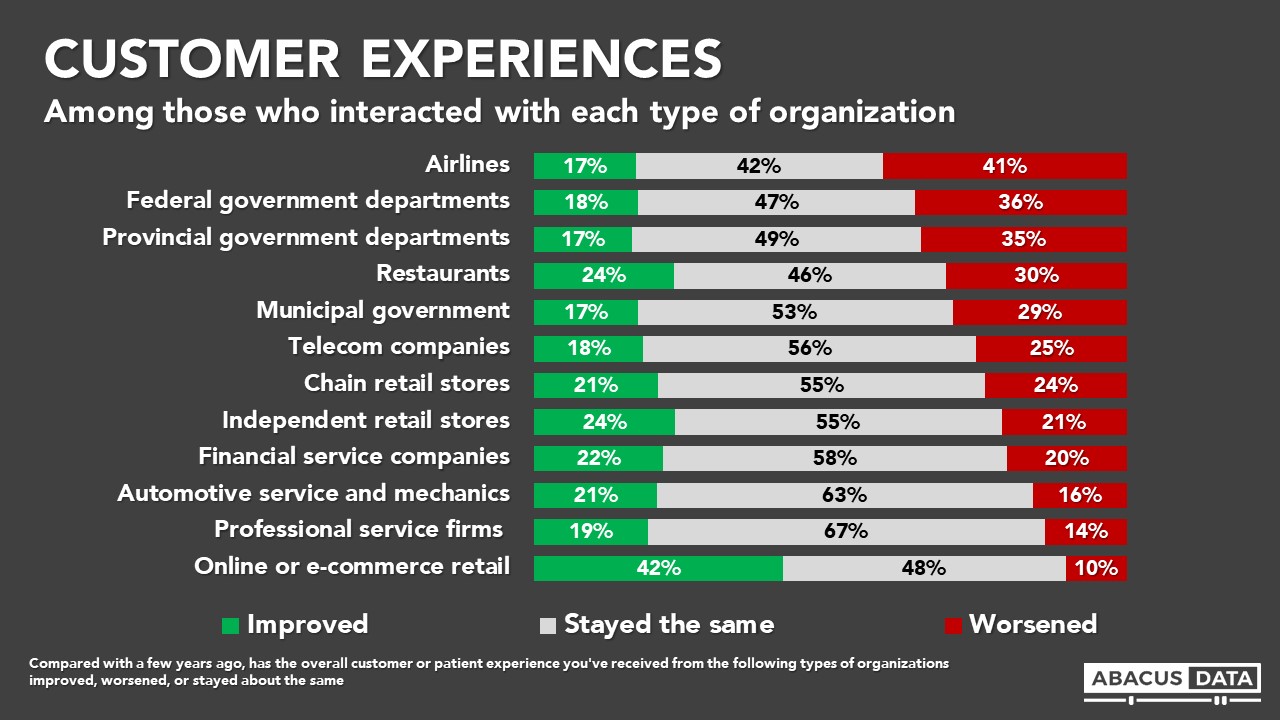

I asked respondents: “Compared with a few years ago, has the overall customer service you’ve received from the following types of organizations improved, worsened, or stayed the same?”

For the most part, Canadians feel that service quality has stayed about the same. Service evaluations of airlines, government departments, and restaurants are worst, while many people feel that the experience online or through e-commerce has improved.

There’s a lot to unpack in these numbers but for me what stands out is that businesses who have faced labour shortages and severe changes to the overall experience (think restaurants and airlines) are seen as weaker while e-commerce and online retailers have been able to improve on the experience overall. This means that the acceleration in e-commerce use over the course of the pandemic may stick around, as consumers met an improving experience while brick-and-mortar retailers were static and constrained by capacity restrictions, social distancing, and other COVID-created challenges.

THE SHORTAGE ECONOMY: CAN GOVERNMENTS DO ANYTHING?

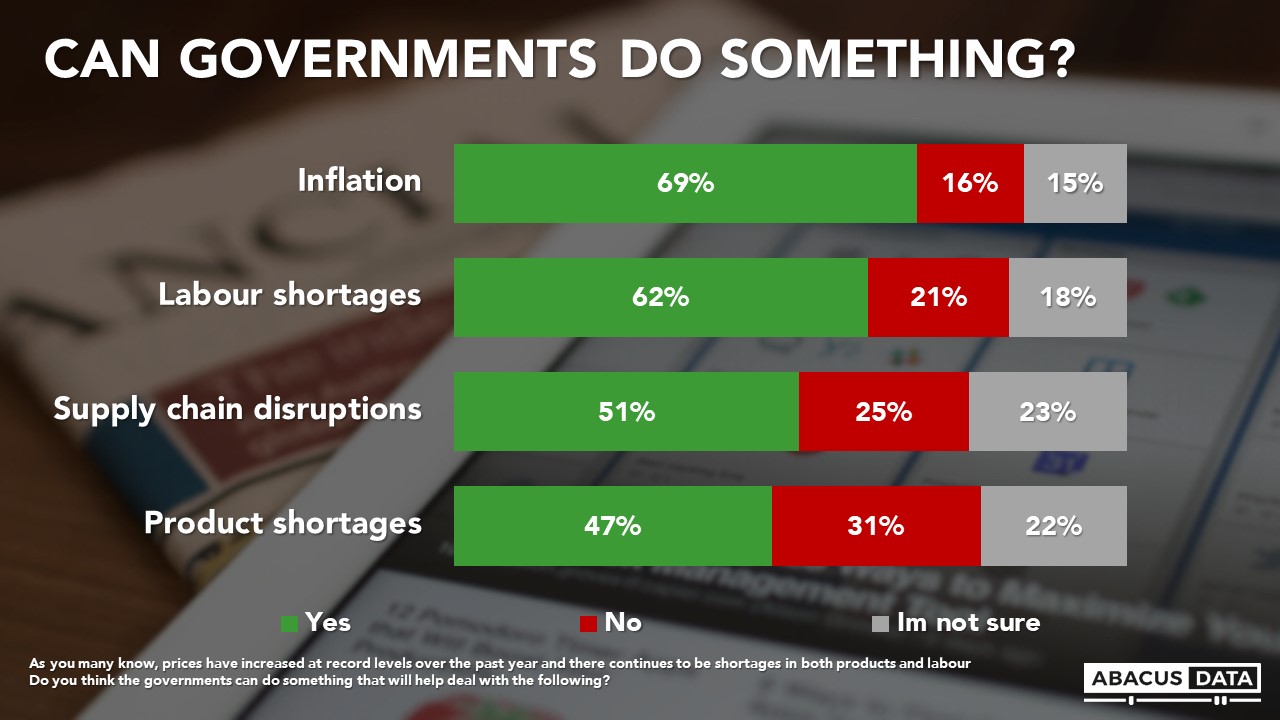

The bad news, beyond the health, social, and economic disruptions caused by the pandemic, is that citizens believe governments can do something to help deal with inflation, labour shortages, and even supply chain disruptions. Whether or not those expectations are misplaced, the perception that government intervention can help solve these issues means that governments and political leaders need to be seen caring about these issues and doing something about them.

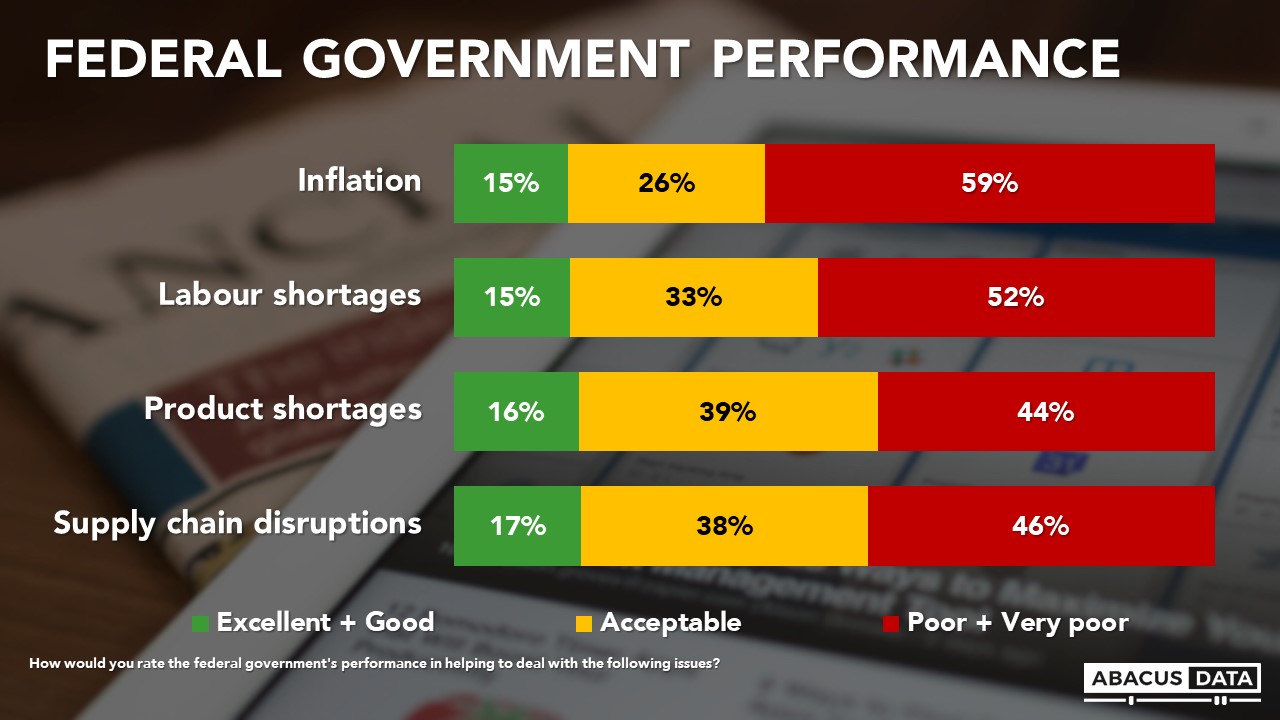

Take the federal government for example. When asked how well the federal government is doing dealing with inflation, labour shortages, product shortages, and supply chain disruptions, views are quite mixed. The federal government gets higher negative evaluations on inflation (59%) than the others. But in no area do more than 17% feel the federal government is doing an excellent or good job.

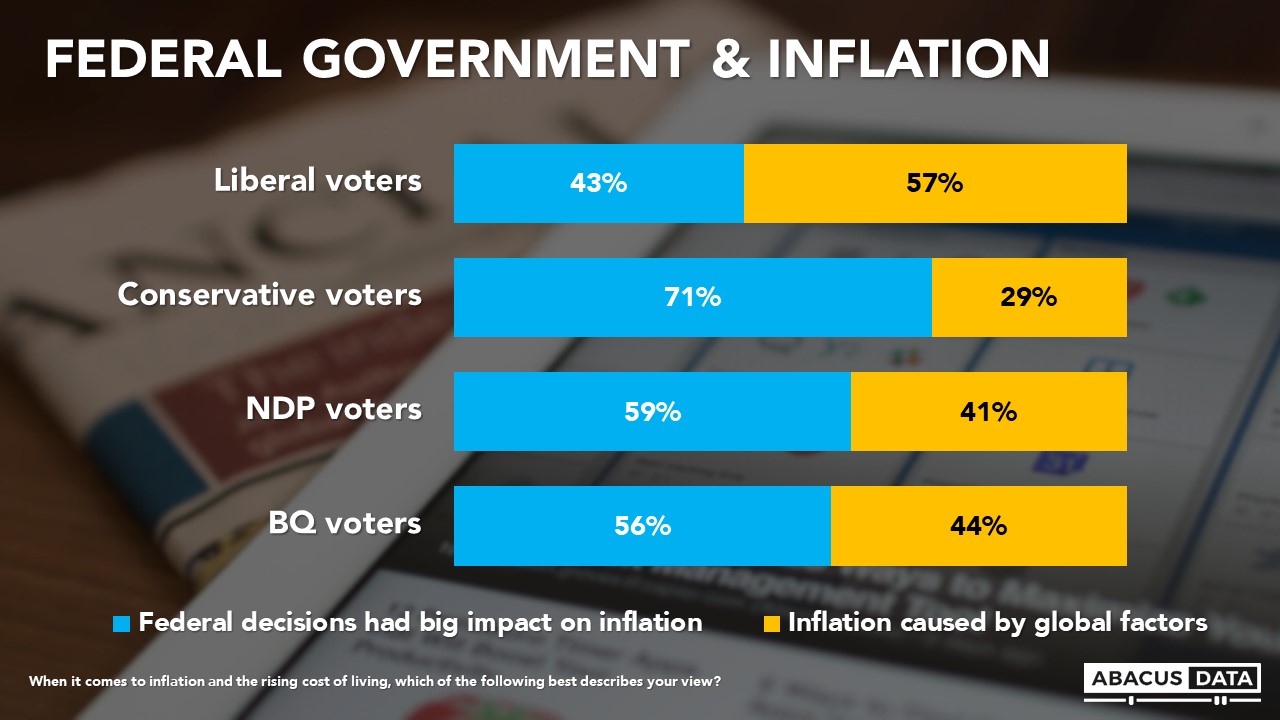

When it comes to inflation specifically, do Canadians think the federal government decisions impact inflation as the Conservative opposition has been claiming?

Well, most do. When asked to choose between two statements, 58% felt federal government decisions have had a big impact on inflation in Canada while 42% felt inflation “is being caused by global factors outside the control of the federal government.” In reality, I assume both could be true but I was interested to see where the public was more likely to fall.

And while supporters of the opposition parties are more likely to think the federal government did have a big impact on inflation, 4 in 10 Liberal voters feel the same way, suggesting this view isn’t entirely caused by partisanship.

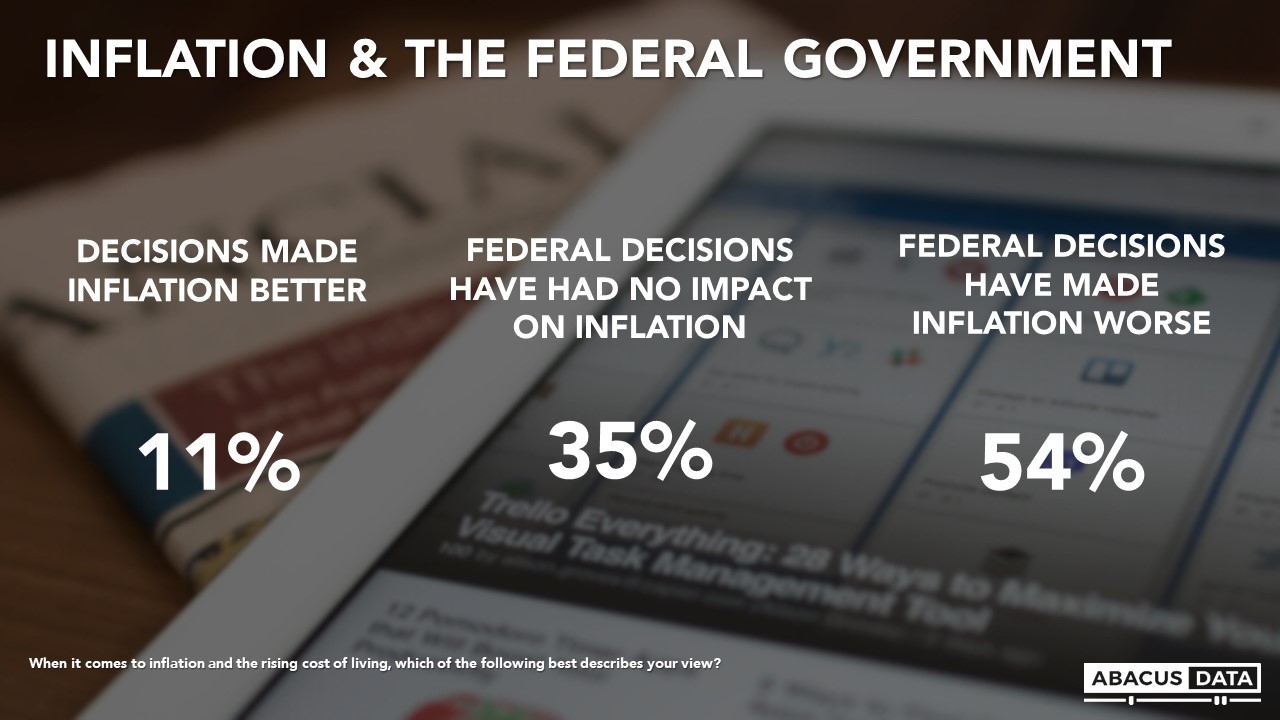

So, if most think the federal government had a big impact on inflation, do people think they have helped or hurt the situation? Most (54%) think federal government decisions have made inflation worse compared with 11% who think its decisions have made inflation better.

In total then, 41% of Canadians believe the federal government has had a big impact on inflation and has made it worse. More troubling for the Trudeau government in all of this – 17% of these folks voted Liberal in 2021 and represent 7% of the electorate.

So what’s the best policy? I’ll leave that to the experts. But from the public’s perspective, when asked whether increased prices for goods and services or increased interest rates would be worse, increased prices won by a long shot. 72% said increased prices would be worse for them personally compared with 17% who felt increased interest rates would be less desirable. Those who own a home and those with higher incomes were slightly more likely to fear interest rate hikes, but even among those groups, price increases were perceived to be the greater pain point.

THE UPSHOT

Abacus Data CEO, David Coletto:

The shortage economy is clearly here. Labour shortages, burned-out workers, and supply chain disruptions are part of the everyday experience for Canadians. Millions haven’t been able to buy the bike, fridge, or new sofa they wanted or needed and many feel the customer service they’ve received from their favourite restaurant, airline, or retailer has gotten worse.

How do leaders respond to this new economic and consumer/citizen opinion environment?

First, I think we all need to lead with compassion and engagement. While there is no Great Resignation in Canada, employees and workers are more powerful than they have been in a long time. More and more, especially younger workers, are looking to be fulfilled at work. They want their work to mean something. They want or even demand employers who care, listen, and respond compassionately. Engage more regularly with your teams and workforce. Measure their attitudes and perceptions and demonstrate you’re listening.

Second, I think all businesses – whether in retail, food service, or even professional or financial services – need to approach customer service with a hospitality mindset. Take a page from a legend, restauranteur Danny Meyer, and empower your teams to deliver enlightened hospitality to your clients, suppliers, and stakeholders. Your organization will be facing consumers, customers, and clients who will be asked to pay more and often for less. Improving the experience is critical. To do so, you have to understand what they want, what they expect, and how best to deliver value in a shortage economy.

Finally, for policymakers and political leaders – ignoring a problem because your choices had very little impact on the problem is not good enough. The public expects empathy and responsiveness from our government and elected representatives. If people say the cost of living is a real problem, don’t explain it away. Respond with something. For the Trudeau government, most already feel it can impact inflation and almost half think it has made things worse. If you continue to ignore or ineffectively respond to what people are feeling, they will look for someone else who doesn’t.

Don’t forget to tune into my TEC Canada webinar on this subject today or reach out if you have any questions or would like to connect.

METHODOLOGY

The survey data used in this study is from a national online survey of 2,210 Canadian adults from January 7 to 12, 2022. A random sample of panelists were invited to complete the survey from a set of partner panels based on the Lucid exchange platform. These partners are typically double opt-in survey panels, blended to manage out potential skews in the data from a single source.

The margin of error for a comparable probability-based random sample of the same size is +/- 2.1%, 19 times out of 20.

The data were weighted according to census data to ensure that the sample matched Canada’s population according to age, gender, educational attainment, and region. Totals may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

Abacus Data follows the CRIC Public Opinion Research Standards and Disclosure Requirements that can be found here: https://canadianresearchinsightscouncil.ca/standards/

ABOUT ABACUS DATA

We are the only research and strategy firm that helps organizations respond to the disruptive risks and opportunities in a world where demographics and technology are changing more quickly than ever.

We are an innovative, fast-growing public opinion and marketing research consultancy. We use the latest technology, sound science, and deep experience to generate top-flight research-based advice to our clients. We offer global research capacity with a strong focus on customer service, attention to detail and exceptional value.

We were one of the most accurate pollsters conducting research during the 2021 Canadian election following up on our outstanding record in 2019.

Contact us with any questions.

Find out more about how we can help your organization by downloading our corporate profile and service offering.